201 Howell Avenue

Address

201 Howell Avenue Brooksville, FL 34601

Year Built

1975

First Owner

Mid-State Federal Savings and Loan

201 Howell Avenue, Brooksville Hardware, Old Brooksville in Photos (Around 1905)

201 Howell Ave, Brooksville Hardware, Re-exposure of Fire (Around 1912)

Photo taken by Brooksville Photographer AA Haskell.

From Jefferson St looking North on Main St. Brooksville Hardware can be seen in the middle of photo. This is now the location of City Hall Building. Photo from 1911

201 Howell Avenue, Standard Oil (1936)

201 Howell Avenue, First Federal

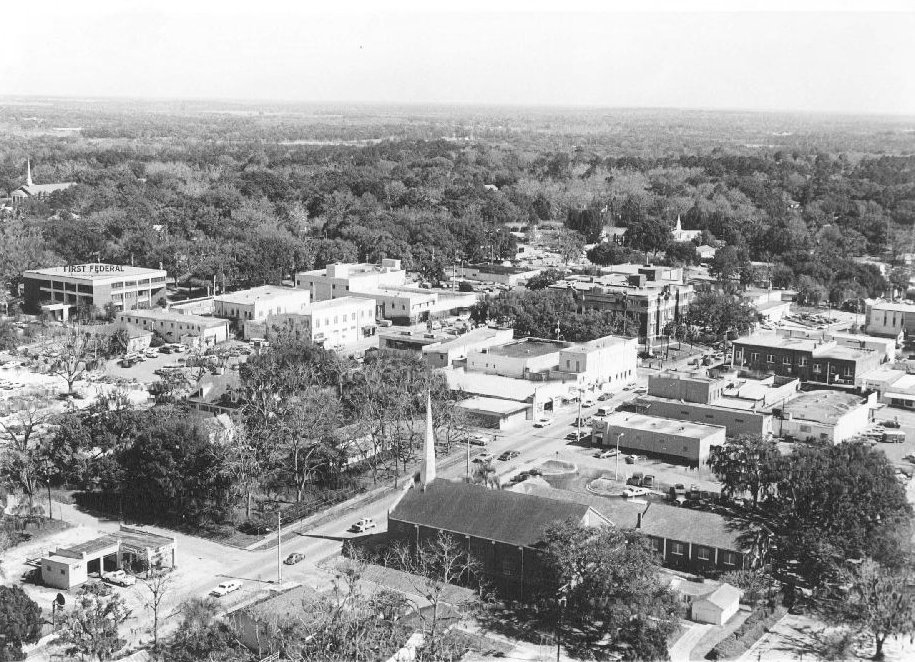

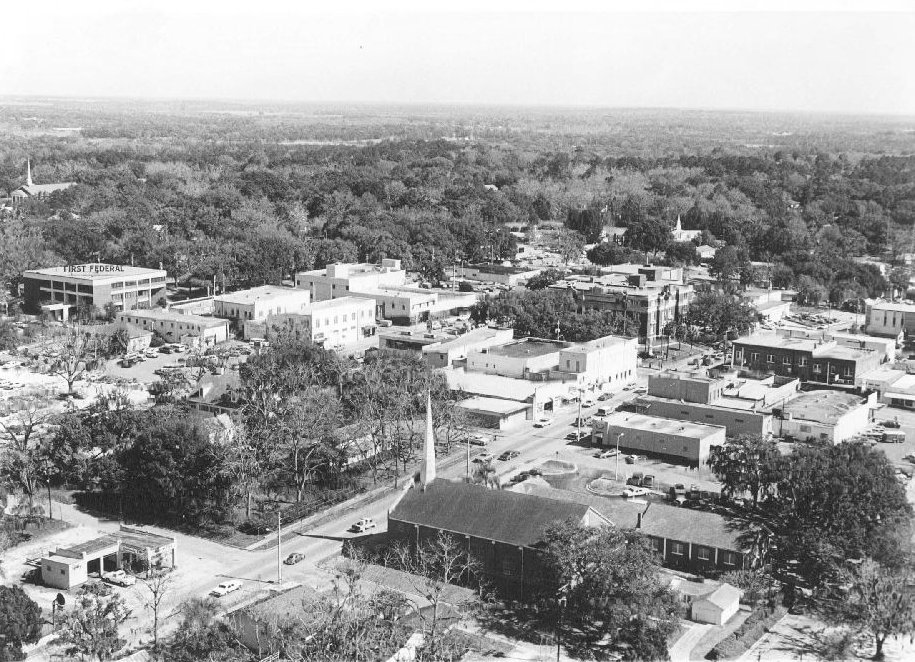

Aerial shot of Brooksville. First Federal Bank can be seen top left. This building is now home to City Hall and Hernando County property appraiser.

201 Howell Ave, City Hall Dedication (1996)

201 Howell Avenue, Jennifer Battista (1996)

201 Howell Ave, Mayor Pat Brayton speaks at City Hall dedication (1996)

201 Howell Ave, City Hall Dedication (1996)

201 Howell Avenue

Learn More about the Walking Tours

-

The Flame of Brooksville: Julia Jinkens’ Olympic Legacy

In the heart of Hernando County, where the sun casts golden rays over the rolling hills of Brooksville, Florida, a small town’s spirit burned brightly in the summer of 1996. Julia Jinkens, lovingly known as “Granny” or “Mom” Jinkens, carried the Olympic torch through her beloved community during the relay for the Atlanta Summer Olympics. Her moment in the national spotlight wasn’t just a personal triumph—it was a celebration of Brooksville’s tight-knit soul, its unsung heroes, and the power of one woman’s boundless love for her neighbors.

Julia’s story is one of quiet dedication, woven into the fabric of Brooksville like the purple and gold of Hernando High School, colors she cherished until her final days. Born with a heart for service, she moved to Brooksville in 1965 with her husband Joe and their three children, planting roots that would grow deep over nearly five decades. By the time she was selected as a torchbearer, Julia had already become a local legend, not for fame or fortune, but for her tireless work in schools, sports fields, and community centers. Her selection as a torchbearer, as noted in a Tampa Bay Times article from July 4, 1996, was a nod to her as a community leader; her name, whether spelled Jenkins, Jinkens, or Jinkins, was synonymous with selflessness.

Picture the scene: the Olympic flame, a symbol of unity and excellence, flickering through Brooksville’s streets, with locals gathered at Pasco-Hernando Community College to cheer. Julia, then in her early 70s, held the torch high, her steps steady with the weight of her community’s pride. The 1996 Atlanta Olympics torch relay, which saw over 10,000 bearers carry the flame from Greece to Georgia, was designed to honor everyday heroes. Julia fit the bill perfectly. Her life’s work—over 40 years in school cafeterias, 15 years providing after-school care at Hernando Christian Academy, and countless hours volunteering—made her a natural choice. She was the woman who opened milk cartons for kindergartners, rewarded good behavior with Dollar Store trinkets, and worked the concession stand at Hernando High football games for four decades, all while earning the nickname “Granny” for her nurturing spirit.

But Julia’s impact went beyond the everyday. She was a dreamer who made things happen. In 1976, she rallied funds for the Hernando High band to march in Washington, D.C.’s Bicentennial parade. In 1987, she ensured Jerome Brown’s parents could attend the Fiesta Bowl in Arizona. By 1991, she was raising money for a local basketball team to compete in Ireland, and in 2000, she helped send John Capel’s parents to the Sydney Olympics. Her efforts even touched the stars, as she organized a hero’s welcome for Army helicopter pilot Bobby W. Hall II in 1995. Julia didn’t just support her community—she built it, brick by brick, celebration by celebration.

Perhaps her most heartfelt connection was with Jerome Brown, Brooksville’s NFL Pro Bowl Defensive Lineman and a local icon. Their bond was so deep that Brown wore a T-shirt proclaiming, “Have you seen my other mother, Julia?” Their relationship, highlighted in both the Tampa Bay Times and Hernando Sun, showcased Julia’s role as a mentor and maternal figure to the town’s youth. Brown’s success on the field brought pride to Brooksville, but it was Julia’s guidance off the field that helped shape his legacy. Her work to establish the Jerome Brown Community Center, where she hosted alcohol-free Tangerine Drop New Year’s Eve parties, cemented her as a guardian of the town’s future.

When Julia carried the Olympic torch, it was as if Brooksville itself was running alongside her. Her moment on the national stage put a spotlight on a small town where community isn’t just a word—it’s a way of life. As Lara Bradburn, a City Council member, said, Julia was “the greatest cheerleader for our youth in county history.” Jim Kimbrough, chairman of SunTrust Bank/Nature Coast, echoed this, praising her boundless impact. Her race-blind approach to helping others, as noted in her 2012 profile, made her a beacon of inclusivity in a town that valued her heart above all.

Even as her energy waned in 2012, Julia’s spirit remained vibrant. That year, she downsized to a home at Clover Leaf Farms with her son Timmy, who took care of her in her sunset years, joking, “You know I couldn’t be too far from the purple and gold.” Her retirement from community roles at age 91, after serving as a part-time waitress and goodwill ambassador at her son’s Red Mule Pub, marked the end of an era—but not the end of her legacy. Nominated for the Great Brooksvillian award, Julia’s story continues to inspire, a reminder that one person’s flame can light up an entire town.

Julia Jinkens didn’t just carry the Olympic torch—she carried Brooksville’s hopes, dreams, and pride. Her legacy burns on in the hearts of those she mentored, the youth she championed, and the community she loved. In a world that often celebrates the loudest voices, Julia’s quiet strength reminds us that the truest heroes are those who give everything for the people around them.

Citations

“Spirit Ablaze.” Tampa Bay Times, July 4, 1996. https://www.tampabay.com/archive/1996/07/04/spirit-ablaze/.

Cotey, John C. “Let Me Tell You a Little about Julia ‘Mom’ Jinkens.” Tampa Bay Times, June 10, 2012. https://www.tampabay.com/news/humaninterest/let-me-tell-you-a-little-about-julia-mom-jinkens/1233000/.

Marrero, Tony. “Big Change Comes, Gently, to Brooksville’s Red Mule Pub.” Tampa Bay Times, January 25, 2015. https://www.tampabay.com/news/business/big-change-comes-gently-to-brooksvilles-red-mule-pub/2267685/.

“Local Legend Jerome Brown.” Hernando Sun. https://www.hernandosun.com/Local-legend-Jerome-Brown.

“Torch Bearer.” Sun Sentinel, December 23, 2001. https://www.sun-sentinel.com/2001/12/23/torch-bearer/.

-

Fort Dade Avenue – A Journey Through Time

Welcome, friends, to Fort Dade Avenue, a road that winds through Brooksville’s heart and carries whispers of history beneath its shaded canopy. Starting in the bustling downtown, this street stretches into a serene, tree-lined path, passing historic cemeteries and evoking the legacy of a pivotal event—the Dade Massacre of 1835. Named for Major Francis L. Dade, whose ambush by Seminole warriors sparked the Second Seminole War, this avenue is more than a roadway; it’s a bridge to Brooksville’s complex past, blending tales of conflict, community, and resilience. Let’s stroll along and uncover its stories.

Begin in downtown Brooksville, where Fort Dade Avenue pulses with the town’s vibrant history. As you move westward, the urban hum fades, and the road transforms into a picturesque canopy, with ancient oaks and moss-draped branches forming a natural tunnel. Along the way, you’ll pass several cemeteries, a resting place for many prominent African American residents like Dr. Sheldon Stringer, the county’s first Black physician, and others who shaped the community’s cultural fabric. These sacred grounds remind us of Brooksville’s diverse heritage, where every headstone tells a story of struggle and triumph.

The avenue’s name honors a tragic moment that reverberated far beyond Hernando County: the Dade Massacre. On December 28, 1835, Major Francis Langhorne Dade led 110 U.S. soldiers—drawn from the 2nd Artillery, 3rd Artillery, and 4th Infantry Regiments—from Fort Brooke (now Tampa) to reinforce Fort King (near modern Ocala). The U.S. government, under the Indian Removal Act of 1830, was pressuring the Seminoles to leave Florida for Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), sparking fierce resistance. After the Treaty of Payne’s Landing in 1832, which many Seminoles rejected, tensions boiled over. That morning, about 50 miles from Fort King near present-day Bushnell, 180 Seminole and Black Seminole warriors, led by chiefs Micanopy (also known as Hubutta Hajo or Crazy Alligator), Jumper, and Alligator (Halpatter Tustenuggee), ambushed Dade’s column in a pine forest.

The attack was meticulously planned. Seminole scouts had shadowed the troops for five days, waiting for the right moment. Expecting an assault at river crossings, Dade relaxed his guard in the open hammock of oaks and palmettos. At around 9 a.m., Chief Micanopy fired the first shot, killing Dade instantly as he rode on horseback. A storm of bullets followed, felling half the soldiers in the initial volley. The survivors scrambled to build a log breastwork, but the Seminoles’ guerrilla tactics overwhelmed them. By noon, only three soldiers—Privates Ransom Clarke, Joseph Sprague, and Edwin DeCourcey—survived, with DeCourcey killed the next day. Clarke, despite severe wounds, crawled 60 miles back to Fort Brooke, leaving a harrowing account of the battle. The Seminoles lost three men and had five wounded, a stark contrast to the near-total loss of Dade’s command.

The massacre, also called Dade’s Battle, ignited the Second Seminole War (1835–1842), the longest and costliest U.S. Indian war. On the same day, Seminole leader Osceola killed Indian Agent Wiley Thompson at Fort King, signaling a coordinated resistance against forced removal. The ambush sent shockwaves across the nation, exposing the Seminoles’ resolve and the challenges of U.S. policy. For the Seminoles and their Black allies, it was a victory against oppression; for the U.S., it was a call for retaliation. The soldiers’ remains, initially buried at the site, were later reinterred in 1842 under coquina pyramids at St. Augustine National Cemetery, a solemn tribute to the fallen.

Fort Dade Avenue’s connection to this event is more than symbolic. It reflects Brooksville’s place in Florida’s turbulent history, where conflicts over land and freedom shaped the region. The massacre’s legacy lives on at the Dade Battlefield Historic State Park in Bushnell, established in 1921 as a National Historic Landmark. Each January, reenactments bring the battle to life, with musket fire and interpretive talks honoring both sides’ perspectives. The park’s museum displays artifacts like Seminole weapons and soldier uniforms, offering a glimpse into 1835’s harsh realities.

An unexpected layer of this story lies in the role of Louis Pacheco, Dade’s guide, a Black man enslaved by a nearby planter. Pacheco, secretly allied with the Seminoles and Black Seminoles, alerted the warriors to Dade’s route, enabling the ambush. His actions highlight the complex alliances of the time, as escaped slaves found refuge among the Seminoles, fueling tensions with slaveholding settlers. This interplay of race, resistance, and survival adds depth to the massacre’s narrative, showing how personal choices shaped a national conflict.

As you travel Fort Dade Avenue, notice how it connects Brooksville’s past and present. The African American cemetery along the route, with graves of community pioneers, speaks to resilience amid adversity, much like the Seminoles’ stand in 1835. The avenue’s canopy, shading historic homes and quiet stretches, invites reflection on a town forged by triumph and tragedy.

Stand here and imagine the distant echo of musket fire, the courage of Seminole warriors, and the resolve of Brooksville’s diverse residents who built a community through turbulent times. Fort Dade Avenue is a path through history, linking us to a moment that changed Florida forever.

Citations

“Brooksville Cemetery,” Hernando Historical Museum Association, https://www.hernandohistoricalmuseumassoc.com/.

“Tour of Historic Brooksville, Florida,” Florida Historical Society, https://floridahistory.org/brooksville.htm.

“The Brooksville Raid,” ExploreSouthernHistory.com, https://www.exploresouthernhistory.com/brooksvilleraid.html.

“Dade Battle,” Florida State Parks, https://www.floridastateparks.org/parks-and-trails/dade-battlefield-historic-state-park.

Logan Neill, “Brooksville Raid Helped Union in Civil War 150 Years Ago,” Tampa Bay Times, July 10, 2014, https://www.tampabay.com/news/humaninterest/brooksville-raid-helped-union-in-civil-war-150-years-ago/2187912/.

Frank Laumer, Dade’s Last Command (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 1995), 106.

“Dade Massacre,” Florida Historical Society, accessed April 15, 2025, https://myfloridahistory.org/dade-massacre.

John K. Mahon, History of the Second Seminole War 1835–1842 (Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press, 1967), 106.

“Dade Battlefield Historic State Park,” Trail of Florida’s Indian Heritage, https://www.trailoffloridasindianheritage.org/dade-battlefield-historic-state-park.

“1835’s Deadly December: The Story of the Dade Massacre,” Florida Seminole Tourism, December 13, 2024, https://floridaseminoletourism.com/1835s-deadly-december-the-story-of-the-dade-massacre/.

Joshua Reed Giddings, The Exiles of Florida (Columbus, OH: Follett, Foster and Company, 1858), cited in “J. R. Giddings’ Account of the Dade Massacre,” World History Encyclopedia, February 16, 2025, https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2256/j-r-giddings-account-of-the-dade-massacre-of-the/.

“Hernando Historical Museum Association,” Hernando Historical Museum Association, https://www.hernandohistoricalmuseumassoc.com/.

The Architecture

Contemporary style with a flat roof, fixed ribbon windows.